Follow Us

Services

- Adapt

- Services

Education

Treatment and Rehabilitation Unit

Child and Parents in Partnership

Training and Capacity Building in the Community

Work Training Unit and the Skills Development Centre

Expansion of Services

Economics and Sustainability

Research and Transformation of Ideology

Policy and Macro-level Change

Results and Outcome

Our future Vision

Education

Outcomes

- With simple modifications in class, we demonstrated that children with disabilities could be educated. Children excelled in academics with the help of concessions granted by the state board of Maharashtra. These concessions were then permitted by most of the examination boards across the country as well as by universities.

- Diagnosis as early as one month began with the mother. Holistic programmes, combining education and treatment were demonstrated under one roof. Early infant clinics, where high risk babies were assessed, helped to create awareness that children with CP must have early detection and continuous management.

- This kind of holistic treatment where doctors, paramedics, special educators, social workers and psychologists worked together with parents took root and began to show results. Regular and continuous treatment trained the child to be independent.

- SSI made a technical contribution, providing a very strong base for children, youth with CP and other physical disabilities.

- A major achievement of SSI was that neurological disability and CP, which had previously not been recognized amongst the government’s classifications, was recognized as one of the 11 official classifications accepted by the Government of India’s ministry of social justice and empowerment.

Treatment and Rehabilitation Unit

The hallmark of this organization is its unique transdisciplinary approach to provide physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, social and psychological development and counseling under one roof.

The organization has now moved from segregated (special school) education to an inclusive education, establishing an inclusive community model of rehabilitation and care.

Results and Outcome

- The latest treatment protocols of Neurodevelopmental Therapy (NDT) and Sensory Integration (SI) therapy were introduced for the first time at SSI within the framework of the social model. This course aims at shifting the focus of the professionals to a combination of skills to look at the child’s social independence along with functional abilities and educational performance. The changing role of the therapist was stressed and the key principles of inclusive education taught.

- Courses by senior, international occupational therapists to develop new strategies for promoting independence and self-reliance for the disabled within the context of the Indian lifestyle and available resources were also conducted. This led to more and more therapists learning about the social model approach which they had never been exposed to within their curriculum of medical schools.

- The ‘eclectic approach’ was maintained with introduction to latest therapy techniques through training courses organized by senior faculty from The Bobath Institute, London, as well as NDT and SI-trained therapists. Therapists were encouraged to attend training courses throughout the country to learn about newer models of therapy and incorporate the knowledge gained into the treatment protocols of the organization.

- Interdisciplinary team approach combining medical, paramedical, educational and socioemotional services were set up under one roof. Due to the fact that all services were offered comprehensively under one roof, large number of children came from different parts of the country.

- New concepts, such as Bobath and Vojta, unknown in the country were introduced. Group therapy and conductive education started by Hungarian neurologist Peto were also introduced. Neuromotor sensory integration programme was created. The importance of the use of the ‘eclectic approach’ was established.

- Parent partnerships were strengthened and parents thus empowered started taking up lead roles around the country. Parents started taking up the responsibility of therapy and due to their empowerment were equal decision makers in the treatment for their child. Parental involvement kept the work on the ground level with a bottom-up approach.

- The ‘Management of Cerebral Palsy and other Physical Disabilities’ course established the much needed therapy training in the country. Therapists came from various parts of the country like Baroda, Bhuj, Cuttack, Bangalore, Mumbai and some came from neighbouring countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh. Through the training of therapists the organization was indirectly impacting the lives of large number of parents and children with CP throughout the country.

- Therapy for children was first of all introduced as being fun and play, with greater emphasis on the interest and motivation of the child, leading to cooperation. It was important to be able to strike a balance between the medical, therapeutic, social and educational needs of the child.

Child and Parents in Partnership

Outcomes

- Parents as professionals changed the dynamics of dealing with parents in India, giving them a status, they lacked earlier.

Lessons

- Professionalism combined with care changed the lives of families with severely disabled children and the new approach of treating parents as important voices to listen to helped to change the situation for hundreds of parents in the subcontinent.

Learnt

- The next decade of service shows that, given the confidence, parents and family members played a key role in expanding services.

Training and Capacity Building in the Community

As a logical progression, we tackled manpower by way of training teachers, therapists, social workers, psychologists and others. National agencies of education were not including special needs in their curriculum. To fill this gap, we began courses in 1977. The first postgraduate diploma course in theeducation of the physically handicapped (namechanged to Postgraduate Diploma in Special Education “Multiple Disabilities: Physical and Neurological in 2003”) was set up in the country in 1978.

The Teacher Training Course aimed to develop the skills and abilities and knowledge to meet the physical, social, emotional needs of persons with physical and neurological disability. With our international partners in the U.K. we developed a curriculum. Since its inception we have trained both national and internationally.

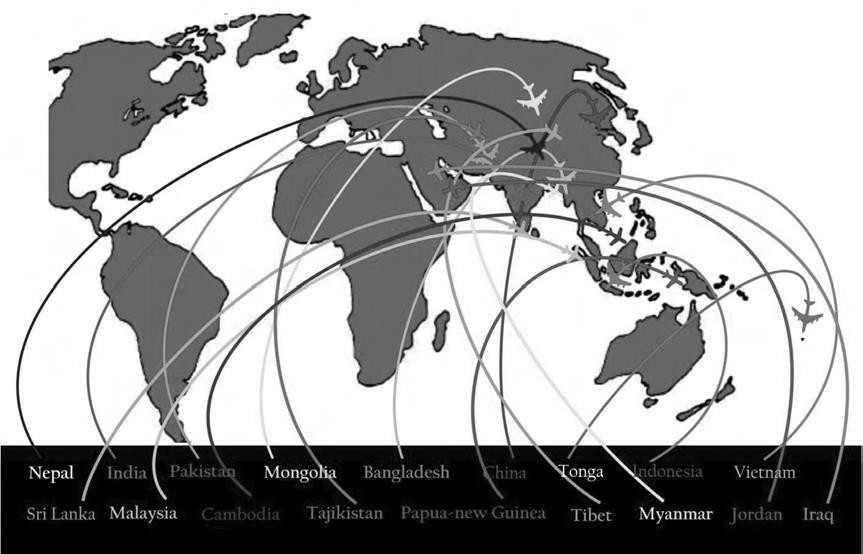

The pre-service Teacher Training Course (TTC) has, since its inception, trained 410 special educators till 2010. Our collaboration with The Women’s Council, U.K and the Institute of Child Health, U.K resulted in the Community Initiatives in Inclusion (CII) course which has trained 300 mastertrainers from the Asia Pacific region.

A path breaking initiative was taken in the fourth decade and that was digitalization of our library services. All were welcome to access our rich experience and expertise of decades and knowledge was democratized. This was Operation Greenstone as the Greenstone Digital Software was used.

Results and Outcomes

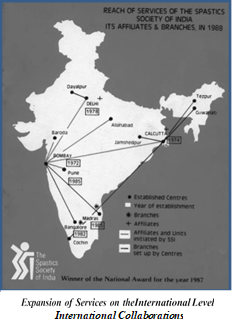

- A method of decentralization began and the result was that full-fledged courses were begun in other SSI’s of Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai and Bangalore. On the national level, the students who had come to Mumbai for training went back to their own states/countries and started services for children with disabilities based on the Mumbai model. Thus, new services began in 18 regions of India including Kolkata, Chennai and Delhi. Our Management in Cerebral Palsy (MCP) alumni now works in hospitals, private clinics, schools and NGOs in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Pakistan.

- Spreading awareness with Government of India agencies, the Rehabilitation Council of India (RCI) requested us to conduct short training programmes and workshops for the State Council for Education Research and Training (SCERT), the District Institute of Education and Training (DIET), zilla parishads, the Department of Education, Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and the Statewide Massive and Rigorous Training for Primary Teachers (SMART-PT). As a result, collaboration took place between DIET, District Primary Education Programme (DPEP), BMC, Maharashtra Prathamik Shikshan Parishad (Maharashtra Primary Education Council–Education Department of the State Government of Maharashtra) and SCERT.

- Orientations were also conducted for students of the various schools and colleges.

- Training was geared towards enhancing and empowering the stakeholders of other mainstream schools, parents, volunteers, community workers and disabled activists.

- Capacity building and empowerment of community teachers were carried out through short-term courses.

- At the national level, two one – month RCI bridge courses for teachers and volunteers working in special schools were also introduced.

- About 10,000 stakeholders have been trained through different courses from 1978.

- This engagement with the state districts and the centre slowly put CP on the map of the country.

Capacity Building in the Community

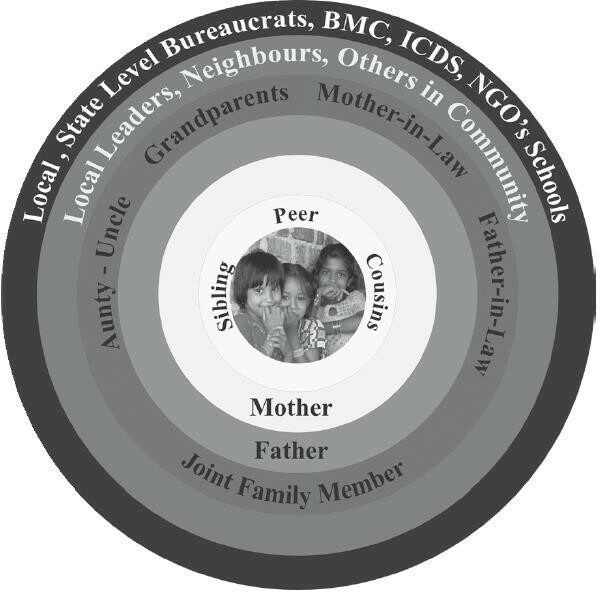

It was time to reach out to the urban slums and we did by extending our services in the largest slum of Asia, Dharavi, the melting pot of India, home to the migrant population. A demonstration model of inclusion in the community, our new model of inclusion wherein disabled children as well as children without disability would study and play together was set up. For the first time, quality education and effective treatment services were accessible to them. We came under the Preventive and Social Medicine (PSM) Department of a municipal hospital in Sion, Dharavi, which worked on identification, early childhood education, treatment, parent training, counselling for children with disability and their families and all the services that was experienced in delivering.

Capacity training began. We trained the community health volunteers (CHVs) of the Health Department in the hospital. These were women who lived in Dharavi and knew the community well. They had undergone training by the PSM Department of the hospital in health, immunization, midwifery and nutrition. The CHV’s role was to make house visits and counsel and advice parents, refer them to hospitals to give birth rather than relying on midwives, to follow up on immunizations and give advice on common ailments like diarrhoea. However, they had received no training in the area of disability. We prepared a one-month module on causes and identification of disability. The CHVs then went into the community and spoke to parents and began referring children to the school. In the first few years, the CHVs had to physically go to individual homes and take the children to school, as the parents all worked and could not bring them to the school on time.

This is how demystification of disability began in the community. The nurses were trained to do physio and speech therapy, moving the focus away from the ‘specialist approach’ to a ‘community approach’, sowing the seeds in the community to take ownership of their programs. Karuna Sadan became a kind of oasis, serving as a Resource Centre for all the children and their families in Dharavi. The community workers were very creative in designing educational aids and toys from recycled material which was cost effective and cost neutral. In fact, the success we have had in training the community workers demonstrated that dis- ability-related needs could be addressed without specialisation.

This reaching out changed the lives of children. We also moved into other slum areas of Mumbai. Our outreach programmes were a great success.

Outcomes:

- The Community was strengthened and empowered

- Women in the Community were trained to be multitasking workers

- The Whole Community Approach was developed

Work Training Unit and the Skills Development Centre

Research showed that people with disability have an intense desire to be economically independent and not be a burden. Systematic and selective skills training was the need of the hour. With this objective we began the Skills Development Centre (SDC) in 1989. Many skills were introduced like carpentry, printing, file making, textile designing, tailoring, ceramic, screen and block printing and horticulture. It was a small ray of hope.

Objectives

- To formalize assessment strategies for employment.

- To develop context-specific models of vocational training and conducting an in-depth analysis of the person’s profile, of his or her strengths and weaknesses, that can be adapted at the urban, slum and national levels.

- To research into various aspects that affect the employment process of persons with disabilities.

Outcomes

- Over 400 models of employment were developed.

- Computer training commenced as a major initiative.

- Through its training programmes, awareness campaigns, research and placement of the disabled in various models of employment, attempted to change the community’s negative thinking about the disabled. A step taken in this direction was a well – researched film on employment entitled Towards Independence, made by Radhika Roy, which is available at SSI library.

- The most important contribution was to move employment opportunities from ‘C’ and ‘D’ category stereotyped jobs, such as basket weaving and telephone operating which disabled adults have been slotted in for decades, to high-end ‘A’ and ‘B’ category jobs.

- A review of a research study showed that although many employers felt that to employ someone with a disability is to employ a liability, the majority felt that the disabled are dependable, conscientious and productive and spending less time off work.

Expansion of Services

Expansion of Services on the National Level: From Schools to Institution Building

The Spastics Society of India (SSI) grew from a small single unit with just three students to a rigorously professional and ardently passionate organization with operations in four cities, providing extensive services for the cerebral palsy (CP) population of India and reaching out to help similar organizations in other countries.

Many of the students did extremely well with the education they received. Many went onto universities for higher studies. Today, some are accountants, lawyers, authors, computer analysts and librarians.

The work was appreciated by the Government of India and it came forward to assist us. Appropriate land was identified and given to the society for its expansion plans. Many policymakers, administrators and politicians visited the first model recommended by us, made suggestions and reached out to support the work.

The first special school for Cerebral Palsy (C.P.) was set up in 1973. It was followed rapidly by several schools being opened in Kolkata, Bangalore, Chennai and New Delhi. Spastics Society of Northern India in 1977, Spastics Society of Karnataka in 1980, Spastics Society of Tamil Nadu in 1980 and Spastics Society of India (Chennai) now Vidya Sagar in 1985 have been formed. Spastics Society of India, Mumbai, as a catalyst, started training of teachers and therapists and skills development. Inclusive education has received a great deal of active propagation with the establishment of a National Resource Centre for Inclusive Education at Bandra, Mumbai. Similarly, the Spastics Societies located in the Eastern, Southern and Northern regions have been very active in training, in providing technical support and networking. (Bowley and Gardner 1980)

We have had many international collaborations and each has enriched our knowledge base. Technical support came in a big way from the UK which has been our partner for longest period of time a When we began the National Job Development Centre (NJDC), our engagement with government helped and the USA was drawn in. The building of infrastructure for skills development for youth and adults with disabilities began with a tripartite partnership, an Indo-American collaboration with the Government of India and NIDRR and the National Institute of Health, Washington DC, provided technical assistance for skills development of

youth and adults with disabilities. This programme was implemented by the Government of India under an Indo-US Intergovernmental Protocol. A visit from the German chancellor Angela Merkel led to an Indo-German collaboration between ADAPT, BMZ (the German development agency) and CBM (Christian Blind Mission) in mapping all out of school children through a very huge project.

International Course: Community Initiatives in Inclusion (CII)

Another international project is a six-month, Asia-Pacific CII course for Master Trainers which began in 2001. The course aimed at training the trainers and planners of community disability services. The course has been supported by the Centre for International Health and Development (CIHD), London and is sponsored by the Women’s Council and ADAPT and over 300 Master Trainers have returned to their countries to promote and support inclusion.

Economics and Sustainability

Economics and Sustainability

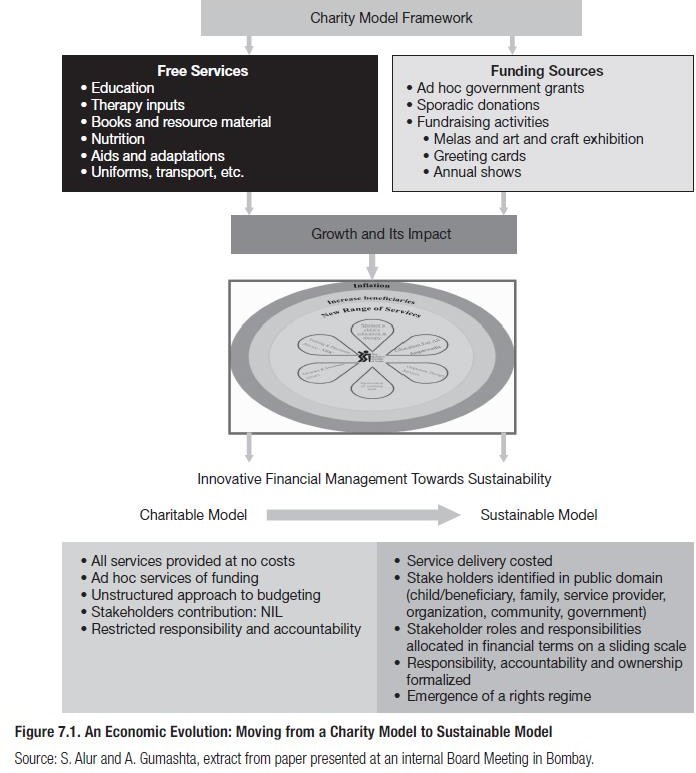

A new approach involving all the stakeholders moved the organisation from charity to entitlement and undertook the multifarious activities of fund raising that took place to make the organization sustainable. The figure given below depicts the movement from a charity to sustainability and the economic evolution of the organisation.

The organization was founded on the core principle of service delivery domain and not for profit Ideology offering services at a time when nothing was known in the country about CP and spastics. It had its roots deeply embedded in these values which form the very basis of the ethos and culture of the organization. In fact, the primary essence of service delivery lies in the fundamental principle that service delivery is based on individual need, delivered in a holistic manner and not related in any way to any contributions by the beneficiary. Four decades ago, the organization’s financial management rested purely on a charity framework. Clearly all services were provided free or at no cost to all beneficiaries. The charity model was of prime importance in laying the foundations of a service non-existent in the country. The key was to reach out to the beneficiaries and convey the methods of delivering education for persons with CP and related disabilities and to empower them.

The charity framework of operations depended on ad hoc donations, small-scale fundrais ing programmes and government grants. We existed with the help of government grant-in-aid for 16 years. The bureaucracy and paperwork involved in operating with government grants was very time con- suming and tough for a handful of staff. It only added to the challenges and financial sustainability became criti- cal. It was vital to shift from a grant-in-aid organization set-up to an independent, non-government organiza- tion (NGO).

The organization evolved its service delivery domain dynamically. On a parallel level, it had to evolve from a complete charity model towards a sustainable one, under the umbrella of a non-profit organization.

The critical issue for NGOs in this sector was to ensure a continuum of services and to make the service sustainable. It was of key importance to move from a charity framework to an entitlement-based one.

In order to ensure sustainability, it was necessary that each of the stakeholders understood the process and contributed. This way they would take ownership.

Over the years, fundraising has evolved in a creative manner, from film premieres to art and craft exhibitions, ‘I Can’ bazaars and melas, greeting cards, charity balls, carnivals and annual concerts. These are fundraising traditions which have carried on remarkably for four decades. A study of the annual reports reflects unique new initiatives each year and the seriousness and importance of fundraising as the organization grew.

International initiatives for Fundraising Were Also Undertaken The constant endeavour to promote international partnerships has been a key input in fundraising for new collaborations and initiatives from early days and these have served as platforms for exchange of ideas, sharing best practices and developing demonstration models and action research projects.

Fundraising is an ideology which has percolated through all stakeholders at all levels at ADAPT through this journey of four decades. We continue to raise funds at the service levels by way of sponsorships, scholarships and earmarked donations. Corpus donations through individuals and foundations are an ongoing part of the revenue generation programme for future sustainability. Project grants with like-minded partners like corporate houses, public sector companies and foundations has been a key outcome of the CSR initiative which has strengthened over the years.

Outcomes

The main principle has been family and community involvement. This is based on the broad philosophy of inclusion to draw in all participants in the community and using the resources of the various stakeholders in a unique way through melas, exhibitions and concerts. It has been a crucial stepping stone for this ever-growing organization to venture into new initiatives and has resulted in invaluable family participation and community participation.

- Community participation through individual sponsorships and scholarship provisioning support has evolved over the years as a part of the service level fundraising along with family participation within the sustainability framework.

- The service providers generate and attach value to the services delivered, bridging accountability and responsibility. The balance is underwritten by SSI.

- Raising revenue through various imaginative ways has supported the organization.

- Every stakeholder is an active participant in the financial viability and sustainability of our inclusive ideology. This remains the core of our continuity of services and sustainability for more than four decades now.

- Revenue generation and appropriate financial management emerged as a core activity to support financial sustainability.

- A planned programme of revenue generation for both corpus (restricted funds) and operations was set up and continuous financial management of budget and cost control was done.

- Whilst the beneficiary families contribute on a sliding scale, based on their socio-economic status, they also become empowered within a rights regime framework, questioning and assuring quality of service.

- Stakeholder involvement through family and service providers’ participation contribute to service delivery fundraising. Community participation involving individual and corporates contribute to providing the safety net by the parent organization.

- Fundraising initiatives, portfolio management, corporate partnerships and international collaborations have resulted in assigning financial responsibility on a macro level.

- This strong foundation has been a key decisive element in newer initiatives of the organization in the field of developmental work.

Research and Transformation of Ideology

Research and Transformation of Ideology: Shift from Special Education to Inclusive Education

Basic services had been established in the country. Now it was time for an ideological shift. Mainstreaming and integrating children with special needs was the vision of Dr. Alur. Medical model was no longer relevant. In medical model it was all about fixing within the child, but the new social model was about fixing the environment. The trend was to modify the environment and curriculum to suit the need of each child. Not an easy task at all.

Inclusion is:

- A Philosophy: Every person has the inherent right to participate fully in society. Inclusion implies acceptance of differences.

- A practice: An educational process by which all students even with disability are educated together.

- Evolving: Leaning about inclusion leads to acceptance, understanding of needs and differences.

- Rewarding: Disabled people are motivated and Able bodied ones are made more sensitive and accommodative.

The main aim had been to technically, financially and administratively help as much as possible. The idea was to let a hundred flowers bloom; let as many children receive services as possible. We realized that this could be best achieved by decentralizing services.

Research: Invisible Children: A Study of Policy Exclusion (1993–99)

During our work in the slums of Dharavi in Mumbai, Dr. Alur noticed that children with disabilities were not included in the government’s Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), one of the world’s largest preschool services providing basic welfare and psycho-social services through their nurseries or anganwadis for women and children.

This was a violation of human rights and unacceptable. She undertook her doctoral research and examined why and how such a major social policy in the country had omitted the disabled child from its agenda,the socio-cultural attitudes towards disability in the Indian subcontinent and explored the widerhistorical, political and ideological framework in which Indian social policy for the disabled exists and within which the ICDS policy and practice may have become embedded.

Findings

The investigation concluded with the finding that various factors have led to disabled children being left out of the ICDS programmes. The research found that exclusion was rooted in the very formulation of the ICDS policy and programme framework.

Disability was simply not identified or defined in anypolicy. Inthe specific context of the ICDS, although it may have been the intention to include disabled children in the term ‘all’ children, there was a gap between policy stated and policy enacted as the ICDS did not include them in practice.

There was an over-reliance on voluntary action or NGOs to deliver services. The NGOs themselves were part of the problem. They were focused on service delivery, their specialist role and fund raising, while disabled people and their advocates were left politically weak and unable to mobilize more systemic policy change. This had taken the matter out of the public domain and placed it within a charity framework. Negative attitudes, ignorance and a lack of awareness that prevailed towards disability had also contributed to this exclusion out of the programmes of the ICDS (Alur 2003).

International donor agencies had also been ambivalent. Partner international agencies hadfailed to set clear parameters in policy formulation at the outset and had not insisted that national policy-makers target their child-centred health/education programmes to include children with disabilities.

The findings indicated that, due to ill-defined policy objectives during the policy formulation stage, policy remained silent on the issue; not clarifying that ‘all’ meant disabled childrenas well. Implementation strategies for the inclusion of disabled children, therefore, were not worked out, which led to the non-inclusion of disabled children from the programmes.

The ICDS policy of non-inclusion of children with disabilities was symptomatic of a wider malaise in India, preventing children with disabilities from getting access to existing provisions and services available to others: without a clear-cut policy directive from the top, a massive exclusion was perpetuated at the ground level. The absence of a clear policy directive hadleft this segment of the population at a critical 0–5 years. A radical change in approach to the problem had to take place. It was critical to change, but change also had to come from within. Gandhiji said, ‘We must be the change we seek.’ And so began the transformation of SSI in Mumbai, moving towards inclusion.

The National Resource Centre for Inclusion (NRCI): An Overview

The National Resource Centre for Inclusion (NRCI) was set up to work towards inclusion.

The project’s aim was to increase the access of children to educational opportunities irrespective of disability, gender and social disadvantage; promote the exchange of information and ideas on sustainable inclusion policy and practice; develop a cadre of resources (human and technological) to support a sustainable model for the universalization of primary education; and foster community attitudes, professional practices and legislative measures supportive of inclusive education and a social model of disability.

NRCI worked at three levels: The macro level looked at policy, legislation, at the local, state, national, international level which was called the Whole Policy Approach; the mezzo level was the level of the community and was called the Whole Community Approach. The micro level was the level of School Development and Training and this was called the Whole School Approach.

NRCI desegregated its own special schools and developed paradigms of inclusion in community schools, in community hospitals and in regular mainstream schools. Disabled students were placed into regular schools and over 60 partners formed the Forum for Local Inclusive Education.

At the mezzo level, the community was sensitized and the ADAPT Rights Group, an inclusive, cross disability rights and entitlement wing of NRCI was set up to advocate and lobby for persons with disability.

Inputs provided on the macro level resulted in political, legislative structural changes and allocation for inclusive education in the five- year plan of the country,

The work begun by NRCI is being continued to embed inclusion within the system.

Developing Sustainable Educational Inclusive Policy and Practice: UK, South Africa, Brazil and India—An International Research Study—UNESCO Project (2000)

This collaborative research project was conducted in England, Brazil, South Africa and India. In this study, the term inclusion was used in a broader perspective and referred to all children who faced any barriers to learning.

A policy development area was selected in each of the countries. 2 States of India, Maharashtra and Tamil Naidu were selected. The study was rooted in the deprived areas and the sites represented a cross section of schooling systems.

The main aims were to identify the factors causing exclusion and to maximize the participation of all students within the development area under an education for all paradigm; to build context- based culture specific models of inclusion which were sustainable and to coordinate with the State and Local Authority and draw them into the project to ensure sustainability.

The findings indicated factors that had contributed to the exclusion of children from the education system, among which were child labour, long distances to schools, ineffective teaching and socio-cultural traditions against the girl child and the disabled child.

It was concluded that demonstration of inclusive education and training of teachers was critical and that each region has different context- and culture-specific needs hence appropriate solutions needed to be worked out for each of these.

Developing Inclusive Education Practice in Early Childhood in Mumbai: The Whole Community Approach—UNICEF/SSI Project (2001)

Research shows that the first five years of a child’s development constitutes the most critical period of his or her life. It has also been shown that there are certain critical periods in the child’s life, when he or she learns at an optimal level. Research also reinforces the theory that the most formative years are before the child comes to school. This argument holds true for all children, including disabled children.

At the mezzo level, we began a two-year action research project based in the slums of Dharavi entitled ‘Inclusive Education Practice in Early Childhood in Mumbai, India’ in col- laboration with UNICEF supported by CIDA. This study was aimed at identifying effective practices for inclusive education for children in the 0 – 5 year age group. The paradigm of inclusion was expanded to include children with disability, the girl child as well as socially disadvantaged children.

The study was based on a population of 6238 households of which 600 children were the direct sample of the study. An enriched curriculum was developed to be imparted to the children who were tracked thrice during the project period. Results showed all children with and without disability improved on their developmental scores and the barriers to learning scores in the environment reduced.

Qualitative findings showed the emergence of a whole community approach to inclusive education and the 3 “D’s” for effective intervention were identified. These were demystification, decentralisation and deinstitutionalization. The study thus led to demolishing several myths around disability and also broke the entrenchment that inclusive education needs a lot of resources and is only for rich countries. Several resources on the “how to of inclusion” were produced which have been disseminated to several countries in the Asia Pacific further expanding the scope of inclusive education and human rights in the world.

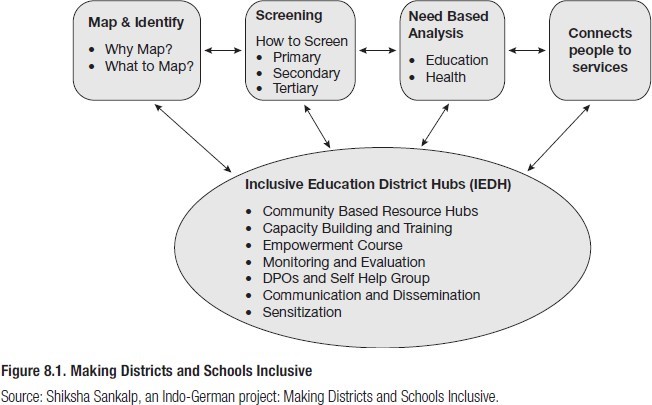

Developing a Sustainable District Model: Shiksha Sankalp (2010–13)

One of the greatest problems faced while estimating anything in relation to disability in India is the fact that figures are hardto come by and when available they varydepending on the definitions, the source, the methodology and the scientific instruments used in identifying and measuringthe degree of disability. Coupled with this isthe lack of the convergence of ministries in providing synergic services, thereby leadingto the malfunctioning of the block resourcecentres (BRCs) and district resource centres(DRCs). To address the need for robust datathat will help bridge existing gaps in services for the disabled, we embarked upon a project that has demonstrated a service delivery model at the district level.

Her Excellency, Dr Angela Merkel visited the NRCI in 2007. Following her visit, Dr Alur and the ADAPT team explored the possibility of seeking support from Germany to develop model community-based resource support centres in two hubs―the urban ‘A’ Ward at Colabaand the rural Pelhar region in Vasai taluka, Thane―that could possibly be replicated across the nation. The project, entitled Shiksha Sankalp, was co-funded by BMZ (Federal Ministry ofEconomic Cooperation and Development), CBM (Christian Blind Mission) and ADAPT.

Shiksha Sankalp seeks to develop a sustainable model for inclusion of children with disabilities within mainstream (public) educational institutions in the two urban and rural catchment areas.

The aim was to determine what structural gaps exist in the delivery of education opportunities for all children particularly children with disabilities and what inputs would be needed (sustainable, replicable, scalable) to meet their needs for basic education in a given jurisdiction

The overall objective was to create a model that supports inclusive education of children with disabilities.

The two catchment areas for the project were the urban ‘A’ Ward of Mumbai district and a rural cluster comprising of 22 villages in Pelhar, Vasai Taluka, Thane district.

The project mapped children with disabilities who were not in school, examined existing educational and support services, and documented what would be needed within this jurisdiction that would help children to access and enter into the mainstream education system.

The key components of the project are mapping, screening, implementing interventions and forming DPOs.

The aim of forming DPOs was to create platforms to facilitate capacity building and training for persons with disabilities. Besides advocacy and sensitization, DPOs were to create awareness on legislative rights and conduct access audits and training programmes for parents and teachers.

Findings from the mapping and screening exercise highlight the need to create an Inclusive District Hub which will connect people with disabilities to the remedial educational, vocational and functional literacy training and therapy services they need. It would also provide resource support in terms of teacher training, empowerment, sensitization of the community, and formulation of Disabled People’s Organisations. Each Hub will provide these services in addition to collection of data of people with disabilities and generate need- based intervention strategies for those identified and screened.

This study helped to develop a sustainable model that can ensure inclusion of children into mainstream schools which can be replicated and scaled across the country.

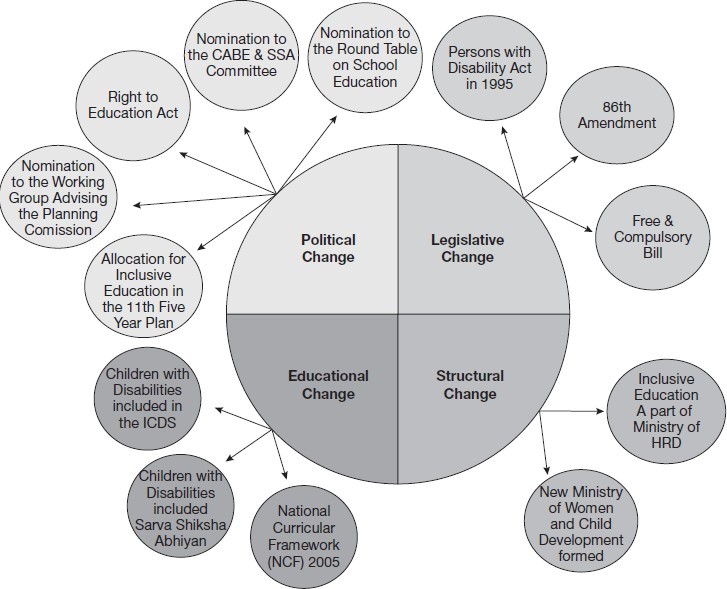

Policy and Macro-level Change

Policy and Macro-level Change: Legislation and Policy

All this while, persons with disability were empowering themselves to learn graduate and master themselves in education but the attitudinal architecture of society and policy was stunted and redundant. The misconception of charity was to be erased and the rights model had to emerge. This needed a strong voice. Ms. Malini Chib took up the matter and the ADAPT Rights Group (ARG) was formed. Through PILs, workshops and advocacy the problems were highlighted and some through the justice system, engagement with the government and sometimes through shift, change was being rolled in. Progress though incremental.

Outcomes

ADAPT intervention were:

- 30 disabled – friendly BEST buses in thecity of Mumbai.

- The High Court added a ramp and a disabled-friendly toilet.

- The backlog for employment for physically challenged or disabled persons has largely filled. The court directed the state government to ensure that the backlog will be cleared no later than six months from 21st of December, 2006.

- The social model of disability was introduced by Malini Chib, Founder student, Trustee through empowerment programmes for persons with disabilities, their families, professionals or ‘allies’.

- ARG also played a key role when dis-abled people were left out of the MumbaiMarathon and for the first time in Indian marathon history people using wheel- chairs were allowed to participate.

Engaging with the Government

Believing that the government, as the main trustee of a nation, must play a major role in bearing responsibility for all its citizens, Dr. Alur began engaging with the Government, with partners from across the country, to influence policy at the national level. The strategy used was more engagement, interaction, persuasion and, of course, pressure as well by way of lobbying and advocacy across the country, through the power of the media, a multi-level strategy using multiple methods.

The strategies used included:

- Regular interaction with key politicians, parliamentarians and policy-makers of all political parties,

- Critiquing of policy measures and documents,

- Sharing constructive suggestions with the government,

- Practical activities to operationalize existing as well as new initiatives,

- Creating a lobby for the implementation of laws that have been passed,

- Interaction with the media,

- Most importantly, addressing the imperative need for financial allocations without which no policy can be implemented.

We networked with the following minis- tries regularly:

- Ministry of human resource development

- Ministryof social justice and empowerment

- Ministry of women and child development

- Ministry of health

- Planning Commission

- Census Commission

- Election Commission

Workshops, Seminars and Conferences

From 1972, there were numerous workshops, seminars and lectures conducted by various specialists from abroad for professionals working in the field of cerebral palsy (CP). These work- shops have been well attended, very well received and have helped greatly in the spread of know-how in the field. Proceedings of many of the conferences were published.

Four International Conferences entitled ‘The North South Conferences’ International Inputs: North South Dialogues I, II, III, IV

On the international level, four international conferences entitled ‘The North South Dialogues on Inclusive Education’ were held to share experiences in inclusion from both the northern and southern paradigms. The North South Dialogue (NSD) was initiated to build a partnership between organizations in India and abroad to learn from each other, exchange ideology and support each other in this journey of inclusion. It was essential for international professionals to be sensitive to differences and diversity of each region and tothe fact that inclusion needs to be culture- and context-specific.

The objectives of the NSD were to examine models of inclusive education which were context- specific to regions in the North and in developing countries in the South as well as to get policy- makers and bureaucrats to attend and learn. The main aim was to put across the stand that every region can do inclusive education but differently from the West and that eachmodel has to be context- and culture-specific to that region. The conferences have been well documented in two publications (Alur and Booth 2005; Alur and Bach 2005).

The far reaching educational change, legislative change, structural change and political change that were an outcome of the efforts with the government are reflected in the figure below.

Figure 9.1. Graphic Display of the Work That Was Done from 2000 to 2014 in Reforming Public Policy

Source: Dr. Mithu Alur

Political Action: A Civil Rights Campaign

Numbering mainly in the poorer areas of the country’s rural, tribal and urban slum areas, the disabled people have no representation in Parliament. The political system clearly did not address this silent and powerless constituency. Nobody has heard their voices—they were not on the agenda of any political party.

We began a campaign for civil rights called The Disabled Vote and promised it to any party that would bring out disability in their political manifesto. Political strength will only come in with representation in Parliament by disabled people.

We first created a political charter, outlining four major demands of people with disabilities.

All India Regional Alliance for Inclusive Education

- Disability issues should be included in the political manifesto of all political parties as well as in their common minimum programme.

- A national disability advisor working under the jurisdiction of the prime minister, within the prime minister’s office, would help bring about effective public–private partnership and monitor implementation of all programmes for the disabled.

- A commitment must be made that 10 per cent of the Member of Parliament’s budget or the MP Lad Fund is spent on disabled people for their education, health and benefitting them.

- Disabled peoples need to be heard in Parliament.

The outcome was that four major political parties included disability issues in their political agendas.

An All India Regional Alliance for Inclusion was set up and has partners across India, who collaborate to lobby for reforms.

Results and Outcome

The Impact: Overcoming Adversity Some Stories

What of Malini Chib?

Malini has a Double Masters’ from the University of London. The First Masters’ was on Women’s’ Studies from the Institute of Education (IOE) under the guidance of eminent Academic Professor Diana Leonard. The second Masters’ was from The Metropolitan College, University of London in Information Management and Technology which made her a fully qualified Librarian. On her return she expanded the library at SSI into a Library and Media Resource Centre (LMRC). Moving the Society’s service delivery mould from Charity to Rights she together with others formed the ADAPT Rights Group (ARG), a unique inclusive group that brought together persons with and without disability battling for their rights. Believing in the larger issues of marginalisation she expanded the Rights Group to include issues dealing with Women, LGBT. Malini is a member of the Research Action Committee of the IRB and one of the Trustees of the Governing Body of the Spastics Society. Malini’s greatest contribution has been the sharing of herself … of having the courage to put out in the public domain her sorrows, her thoughts…of constantly reminding everyone that persons with disability need to be a part of the mainstream and not apart from them…of reiterating the international thinking of ‘Nothing About the Disabled Without the Disabled’.

Vipasha Mehta

Vipasha Mehta was a unique student. She was one of my first students with whom I experimented with an idea that with good, effective teaching (sometimes one gets this with home teaching) you can cover several classes in a short period. She was terribly bright, sharp, intelligent and scored high in her psychological tests. I decided to teach her. I remember for the first time, I used a very broad expanded keyboard which she could handle. The idea was she should be able to express herself independently. She soon picked up what I wanted and we covered ground in leaps and bounds. She finished the syllabi of three standards in 2 years. Initially her communication was poor, but soon she began to assert her newly found independence. Vipasha had earlier been taught in her mother tongue Gujarati. However, it did not take her long to master the English language and within a year she was writing poems in English! She scored very high in her examinations. Vipasha is the only person with CP who has done her PhD and lives independently in Berkeley, California. Her sharp intellect is also manifested in several books of poetry she wrote and I quote below an excerpt!Our future Vision

The Way Forward: A New Vision. A New Tomorrow – To establish The ADAPT International Multiversity, a multidisciplinary and international institution of higher learning that offers post graduate programmes, with high quality teaching, research, and community engagement

The ADAPT International Multiversity

We have essentially been a Knowledge Centre and we are now moving onto becoming a Multiversity. The ADAPT International Multiversity aims to address diversity and inclusion; to develop a cadre of resources (human and technological), to support a sustainable model for higher education.

In addition to teaching and research, the University will discharge other crucial responsibilities, through appropriate resourcing and initiatives, and structures. These include networking with other higher education institutions, nationally and internationally, with a stress on values in education.

The RTE is not being implemented in its true spirit at the ground level. In view of the Indian legislations PDA (1995) and RTE (2009) and in order to close the gap between the UNCRPD mandate and the situation on the ground there needs to be convergence between the special and general school system.

This University will run Open Distance Learning (ODL) and will, over a period of time, be developing a Hybrid Model in partnership with our constituent hubs for a large student enrolment, perhaps in thousands, for the creation of vibrant multidisciplinary communities which are inclusive.

The University will be a multidisciplinary institution of higher learning that offers post graduate programmes, with high quality teaching, research, and community engagement with equal emphasis on teaching and research so that it is a research intensive University.

It will focus on ensuring equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities.